The 2022 Sacramento Nationals: Worst to First in Sacramento!

By Bruce Maiman, Sacramento Nationals 50+ Sunday Division

The NFL has seen it happen nearly every year in the modern era. But chump-to-champ transformations are less common in baseball, especially at the amateur level, and few in the Sacramento MSBL gave much thought, let alone any such chance for the Sacramento Nationals in 2022.

It would be a new squad of 50- and 60-year-olds, built around a nucleus of players fed up with their old team. That team, the CalGiants, had won just six games in four years. Perennial cellar dwellers.

“A living hell,” recalled John Davis, who would become the Nationals’ leading hitter. “Every single week we invented new ways to lose games.”

Management kept telling us, “It’s a rec league,” but going 6-and-60 over four years? It wasn’t like we were those lovable New York Mets of the early 1960s.

The grumbling among players reached such a fever pitch in that fourth year that only two choices remained: mutiny or secession.

“We should just start a new team,” I told my teammates.

Sounds good when you say it fast, but then ya gotta do the work. It was early July. The CalGiants would eventually finish the 2021 season winless.

The “recruitment pitch” was simple: Our guys have been at the bottom of the standings for too long and deserve better.

The MSBL’s Sacramento chapter is vibrant and competitive, with age divisions from 18+ on up for its night league and Sunday league, and there’s a weekday league for guys 60 and over. Some players are well into their 70s. Others play on several teams in different age brackets. And there are always players interested in new teams, new opportunities.

I lost count of how many players turned me down. They were polite about it, with explanations that sounded legitimate.

“I’m already playing on a weeknight team.”

“I prefer to keep my Sundays free.”

“My wife complains I play too much already.”

What they meant, though, was sort of like what Lou Brown said in “Major League” when he got a call at his tire shop to manage the Cleveland Indians.

“Lemme think it over, will ya, Charlie? I got a guy on the other line about some white walls.”

And that was the feeling around the league. No one said it outright but the CalGiants simply had a reputation. A new name was just lipstick on a pig.

Another challenge: competing with other teams for the same players.

One was Dean Mann, a perennial A-list pitcher for the past decade.

“After all the talks I had [with other teams],” he told me, “I began to realize that maybe instead of upsetting an established team’s chemistry, why couldn’t I join a team that wants to sincerely turn things around.”

You keep digging, schmoozing, networking, scouting. A roster began taking shape.

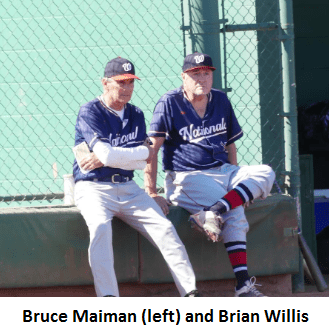

Along the way, Brian Willis called me. A longtime MSBL player and manager in Sacramento and the Bay Area, he’d heard I was putting a team together.

“Can I manage?” he asked.

I was going to do it but said, “Sure,” thinking that would free me up to get more playing time. Instead, I ended up recruiting myself out of the lineup.

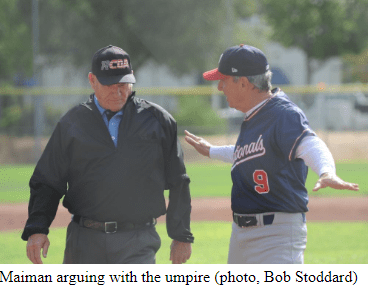

Brian and I had decided to sort of co-manage. The line-up card was his. I’d handle the GM-type stuff, serve as a bench coach, and maybe be a bit of a team psychologist. You’re not just managing players, you’re managing people.

In these roles, Brian and I played sparingly, letting everyone else play before putting ourselves in the lineup.

We had different priorities at first: I wanted to win the whole damned thing; he was more concerned with good chemistry. Some long, tough discussions followed, but we figured out how to make it work.

The team had a rough start to the season.

“We sucked,” said Mann. “Then we shored up. It showed how fast we jelled as a team. Obviously, managing and coaching helped get us there.”

Maybe. Or maybe we just got lucky. We had talent and good baseball IQ, but something else was afoot.

“Every year with the CalGiants, my skills eroded and my production level sank,” recalled Tom Ortiz, a key utility player.

Tom’s season with the Nationals was a complete turnaround. If our league gave out awards, Tom would be the Comeback Player of the Year.

It was motivation, but not in a self-serving way. Instead, players were doing two things: they were playing up to each other’s talents instead of down, and they were playing for each other instead of for themselves. There was trust, reliability, and an understanding that you were doing your best not for yourself but for your teammates, just as your teammates were doing for you. It was knowing that the team was there for you whether you had a good day or a bad one.

“Think about Neil’s season,” observed Nationals’ RBI leader Russ Hayes, about teammate Neil Brolin.

“Here’s a guy who struggled at the start whom we envisioned as a pitcher.” Despite disastrous outings, “the team supported him all the way.”

Neil never balked when he was pulled from the rotation. Instead, said Hayes, “he changed position, stabilized the catcher slot, and became a key contributor when some of us weren’t sure he would even come back given how bad the start of his season was.”

“To me, his season exemplifies all we are about.”

Teammate Manny Perez put it this way: “I came to this team not expecting much as far as wins and losses but mostly from a selfish standpoint of getting more ABs, innings on the mound and behind the plate. Wow, was I completely off base! I quickly realized we had something more than a ‘throw-together team.’ In fact, I couldn’t tell you who is from the old or the new team, it feels like we’ve been playing together for years already.”

After one of our games, the opposing manager asked, “How did you guys get that kind of chemistry?”

Honestly, I’m not sure how. I’m not sure how you can even notice it, let alone where it started. But in an era of analytics, when advanced metrics can determine a player’s exact value, there are still the elusive and nebulous intangibles that go beyond measurable on-field contributions. It has code words like “character,” “culture,” “atmosphere,” “grit.” Whatever “it” was, an all-in approach was taking shape.

“One thing that many on the team may not know,” said Hayes. “During formation, we went through the hard talks about what we all really wanted. You and Brian were on different pages but you guys worked through it, and the team is a reflection of that joint philosophy. Had you two not come together, this could have been a fiasco.”

The league began taking notice. Managers weren’t just complimenting the team. Players started approaching us about next year even though we were barely halfway through the season.

“We knew early in the season that the Nationals were going to be the team to beat if we were going to win our division,” said Mark McGushin, manager of the Sacramento Seals. “They put together a solid team that jelled quickly.”

Sure enough, after a 3-5 start, the Nationals went on to win eight of their last 10 games and clinched the division.

Worst-to-first.

But it came with a price. Down that stretch, the team was struck by a series of misfortunes: Neil’s dad, who came to every game, was diagnosed with cancer. Another player’s 90-year-old mother had to undergo major surgery to survive.

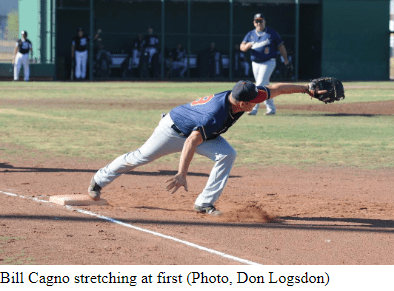

Injuries cropped up like Whac-A-Moles, crippling the heart of the lineup. We limped into the playoffs, playing injured, if at all.

If we were the team to beat, we were no longer the team McGushin said we were, and his Seals beat us to win the championship in the series finale.

No excuses. They deserved it. They are an excellent team and a class act, gracious in victory. The two teams genuinely like each other.

That’s the nice thing about playing in the MSBL. The game bonds players in friendship and mutual respect regardless of team uniforms and division rivalries.

“I’m sure we will be battling with the Nationals at the top of our division for years to come,” McGushin told me.

First, though, a team party once Arizona is done. We will be inviting the Seals as welcome guests.

In asking teammates for their thoughts on the Nationals and our season, many praised the coaches.

“You and Brian have done an amazing job running this team,” said Neil Brolin, one of the old CalGiants. “Your guys’ baseball IQ is so much more than what we have had in the past, yet you listened to us when we had something to say.”

“On a daily basis I see the effort the coaches put forth,” said Perez, a new player, “with emails, texts, and offering their time to put on extra practices for players to stay sharp. I’ve never had that available before.”

I don’t know if I buy all that praise. We managed to put together a team that was good enough to manage itself. We just gave them support when they needed it.

In other words, you don’t build a team. You build people. And then people build the team.

Of course, there are plenty of teams across the MSBL that fit that description. How many were able to do it in one season, I can’t say.

It’s easy to define a successful season in terms of wins and losses. Winning is a great tonic, but it can ring hollow.

“I’ve played on a lot of teams that, on paper, should have been undefeated champions,” said Rob Waldman, one of the Nationals’ quiet leaders. “But when you get a team of ‘I’ guys that play for themselves and their stats, it becomes a cancer. No ‘I’ guys here; just people who, through thick and thin, had everyone’s back, not just their own.”

There’s great satisfaction in defying all expectations, but how this team grew to do that may be its greatest success.

Baseball analytics uses countless metrics for assessing player performance. Like any team, you can break down for the Nationals—and we did—and find room for improvement, which we will.

But there’s no blueprint for assembling a team of “we” guys, and whatever you want to call it, our players believe in it, even if they can’t measure it.

“It was completely my pleasure,” said Perez after I’d thanked him for being part of the Nationals. “I can’t wait to get back to help this team win a championship.”