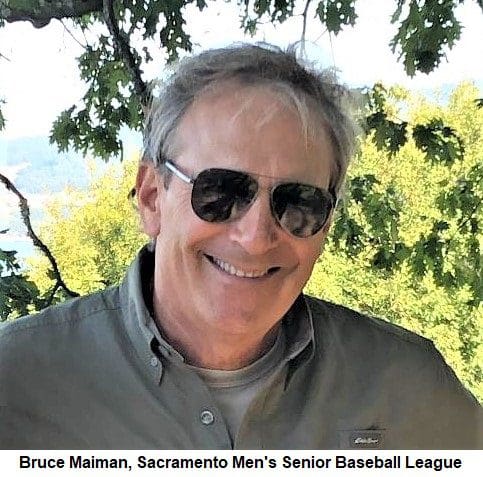

MSBL Veteran Bruce Maiman Describes His Brief Encounters While Delivering the Mail in Loomis, California

By Steve LaMontia, Director of Communications

64-year old Bruce Maiman is a long-standing journalist who has been impacted by career adjustments and is now delivering mail in Loomis, California. He is also a member of the Sacramento MSBL where he plays for the Sacramento Reds and the Giants in the 50’s, on different days, and the Rockies in the 60’s. He is able to log around 75 games per year, as well as making appearances in tournaments. Bruce is now a front-liner in his daily encounters with the people on his route. Yahoo News recently published a story outlining Bruce’ story. We’ll let Bruce tell it to you, along with a reprint of his feature. (Photos courtesy of Jane Burkitt)

The pandemic has special meaning for me. I’m from New York City (and will always be a New Yorker) and have a brother living in Queens who suffers from post 9/11 health issues. He was there, so he’s especially vulnerable.

I’ve been in media for 30 years but over the last several years, as media opportunities have dried up, I’ve hired on at the post office, so I deliver the mail each day. They call us essential workers but I just see it as doing my job. This story is a personal narrative I wrote but it’s less about me, the postal worker, than it is about the Postal Service. It’s not really about what it’s like to deliver mail during the pandemic but more what it’s like for customers to get mail during the pandemic.

There have been a fair number of stories about how the pandemic has hammered the Postal Service but never anything about their customers, how they’re seeing mail delivery in the COVID-19 era. It turns out the nation’s most popular agency has become a sort of lifeline and has provided a certain amount of solace for a shelter-in-place populace. Or as one customer put it, a sense of normalcy during a surreal time.

“I’m a postal worker. In the coronavirus pandemic, I am my customers’ link to the world.”

The other day a perfect stranger came up to me and said, “Thanks for your service. You guys are doing a great job.”

I’m not in the military. I deliver the mail in Loomis, Calif.

While Washington debates the fate of the Postal Service and the fiscal hit it’s taken from the coronavirus pandemic, a remarkable shift has occurred in how people view the mail and their mail carrier in the COVID-19 era.

Over the last six weeks, the friendly waves I receive along my route in Loomis, a rural community dotted with sprawling homes, vineyards and horse ranches, have become more effusive. Smiles are wider. Mailboxes are emptied more frequently, no doubt because stay-at-home orders have people looking for things to do. Conversations with my customers have become lengthier and more personal, tinged with a sense of relief that at least mail delivery remains dependable and stable in what has been an uncertain and unstable time. The interactions my fellow carriers and I have experienced since the pandemic took hold seem almost to have become a coping mechanism for our customers.

“The fact that it’s consistent, that it comes every day, is comforting,” Zack Sanchez, a customer, told me. “Our day has really slowed down. With our 5- and 7-year-old we were involved in four sports and it was nonstop between that and school. Now we have home school and no sports. Getting the mail is one of the major activities of the day.”

We’re seeing, too, small gestures of gratitude: a bottle of wine, gift cards and handwritten notes left in mailboxes expressing thanks. “How ya doin’?” I ask when I see my customers.

“How are you doing?” they respond from a safe distance.

A retiree who affixed a sign on her mailbox that reads “Thank you!” Deb Koss thinks we should get hazard pay.

“I see postal workers as our frontline to keeping everyone else well,” she told me. “You guys bring me my medicine.”

Of course, we’ve also been busy delivering books, stationery, pet food, makeup, clothing, disinfectant wipes, hand sanitizers and, yes, toilet paper. Our office, well stocked with PPE items for each employee, is handling nearly triple the normal volume in package delivery.

We’re also seeing an uptick in something else: personal letters. It’s an interesting development in the digital age when many are connecting virtually through Zoom, Skype and FaceTime.

“A letter is much more intimate than a text or short, terse informational-type stuff,” said Roberta Brosnahan, a retired high-tech VP on my route. “There’s much more introspection. We reflect before we write. Start over again because it wasn’t coming out right the first time. It’s much more human. We’re able to say things we wouldn’t say person-to-person.”

“The mail grounds us,” said Kayo, Sanchez’s wife. “It gives us a physical grounding to the world that the streamlined ones and zeros of email can’t really capture.”

Any uptick in personal letters, anecdotal or otherwise, will likely be short-lived. The digital age has caused a precipitous drop in mail volume. Postmaster General Megan Brennan has told lawmakers that the Postal Service needs a serious infusion of cash — roughly $75 billion over the next several years — lest it run out of money by September’s end, not exactly ideal timing with a presidential election ahead and voters increasingly voting by mail.

As Congress and the president haggle over the future of the Postal Service, Washington has designated its 630,000 employees as essential workers, an increasing number of whom have been stricken by the coronavirus.

As we go about our day, my fellow carriers and I are imbued with a renewed sense of purpose knowing that our customers remain thankful for the work we do and that they still appreciate an institution that has been a part of American life since the country’s founding.

“I teach my seventh graders regularly about knowing how to write a real letter,” a customer named Kathy Brummund said. “I always make a point of assigning a thank-you letter at the end of the school year.” Teaching remotely now, she still intends to assign that letter.