He Just Wanted to Play Catch. They Got Relief from Troubled Times

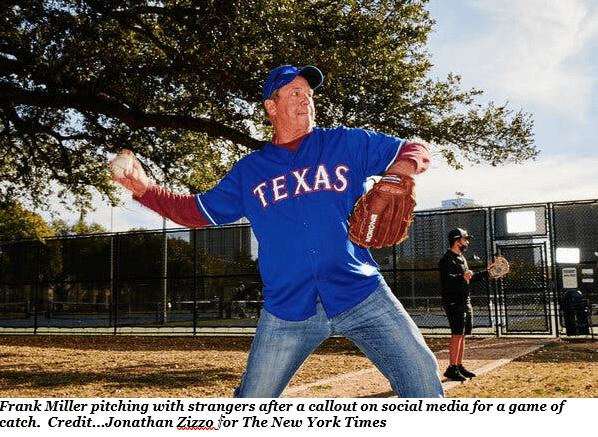

A callout on social media for a game of catch in Dallas drew a varied group of strangers who found escape from society’s turbulence in the most banal ritual.

By Mike Wilson, New York Times

Published Jan. 15, 2021…Updated Jan. 16, 2021

DALLAS — For a couple of days in early January, Frank Miller wandered around his house holding a baseball, practicing the grips for a slider, curve and cutter. He’d read a book about pitching and now he was obsessed.

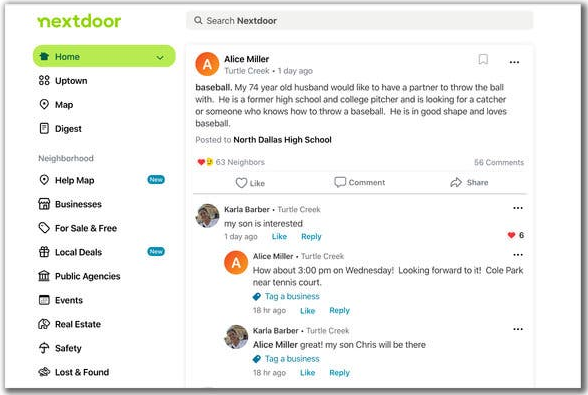

He needed to play catch, stat. So, his wife, Alice, more adept at social media, posted a note on Nextdoor, the neighborhood app.

“My 74 year-old husband would like to have a partner to throw the ball with. He is a former high school and college pitcher and is looking for a catcher or someone who knows how to throw a baseball.” She volunteered that her husband “is in good shape.”

In a world with its cover torn off, the idea of a man in his eighth decade yearning for a baseball buddy seemed to spark something in people.

“My son is interested,” a woman quickly replied.

A steady flow of messages followed.

“I can throw,” a man said.

“I would love to have a catch,” another said.

“What a wonderful way to bring people together and start 2021 with a positive note,” another neighbor wrote. “This makes me smile.”

By confessing his own need, Frank had unwittingly tapped into a longing in others. Not knowing what else to do, Alice welcomed all comers: “How about 3 p.m. Wednesday at Cole Park near the tennis courts?”

They wondered if anyone would actually come.

Not that Frank couldn’t endure it if they didn’t. He is not some husk of a man aching for a life he never had. A retired civil engineer, he plays golf and tennis, spends summers in Michigan, flies a Piper Archer, checks items off the honey-do list. He has a son, a daughter, a stepson and three grandchildren. It’s an enviable life.

But as Jim Bouton wrote in the classic book, “Ball Four,” a lot of people spend a lifetime gripping a ball, only to realize “it was the other way around all the time.”

The game got a hold of Frank Miller in the early 1960s, when he pitched for his high school team in Greenville, N.Y., and then for Lehigh University in Pennsylvania. He can describe with cinematic clarity the grand slam he hit in May of his freshman year — and show you the ball, which he keeps in a box marked “memorabilia.”

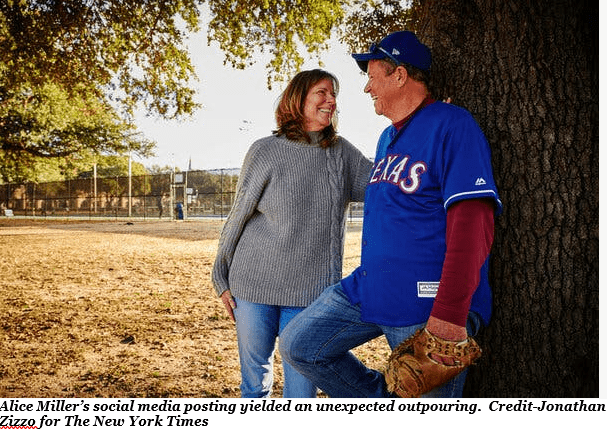

He has visited his enthusiasm upon Alice, his third wife, who knew nothing about baseball when they met 10 years ago. “Frank introduced me to the complexities of the game,” she said, managing not to sound like a hostage.

The Millers were surprised by the response to Alice’s Nextdoor post, but when they thought about it, it made sense. Between the dual curses of politics (“I’ve lost friends,” Frank said) and the pandemic, people are ticked off, scared and solitary.

“I think people want to reconnect a little bit right now,” he said a couple of days before the meet-up.

On Wednesday, he and Alice showed up early at Cole Park, Frank outfitted in a lime green mask, jeans and a Texas Rangers jersey and cap. In his black equipment bag he carried his Nokona glove (a 2019 Christmas gift he’d barely used), four new baseballs as smooth and white as eggs, two older balls, and the Hawthorne catcher’s mitt he bought six decades ago at Montgomery Ward. Earlier in the day, he had used Gorilla Glue to close a tear in the thumb.

A local television reporter had seen Alice’s post and was waiting for the Millers by a park bench. Frank kidded him about his priorities. “Do you know they’re impeaching the president right now?” he said, laughing. Indeed, in Washington at that moment, House members were speaking gravely about enemies, foreign and domestic.

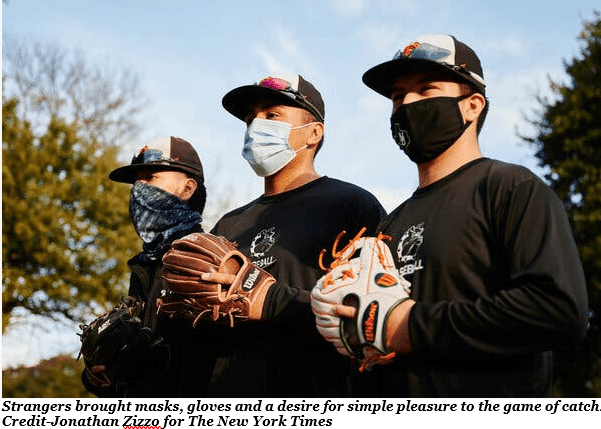

One by one, entering the park from all directions, about 10 more people arrived, many with mitts tucked under their arms. A bearded man in his 30s. Three boys from the North Dallas High School team and the staff member who had encouraged them to come. An older man in a T-shirt that said “ALASKA — The Great Land.” A woman in her 60s who had come just to watch.

The players exchanged hellos and elbow bumps, then formed two lines facing each other in the sunny space between oak trees. The nearby thwacking of tennis balls was joined by the slow, steady rhythm of balls popping into mitts, like the last few popcorn kernels exploding in the microwave.

At 74, Frank short-armed his throws a bit, yet managed to deliver the ball with impressive zip. One of his tosses skipped off the glove of an older man, who then hobbled after the ball, threw it back to Frank on a couple of bounces, and shrugged.

This was Rich Mazzarella, 73, who grew up in Astoria, Queens, worshiping the Yankees and playing in a Scrabble board of youth sports leagues: CYO, PAL, YMCA. He hadn’t thrown in 35 years and — this is unfortunate, but facts are facts — had long since given his baseball gloves to his grandchildren. He had to borrow Miller’s catcher’s mitt to play.

Mazzarella was asked why he came.

“Fountain of Youth,” he said. “The opportunity to do something that I never expected to do again in my life.

He settled into his best catcher’s stance (a little high in the haunches) and caught a few more pitches from Frank, their combined ages about as old as the game itself.

Soon they took a break, their arms wobbly, but the day had gained its own momentum. A few steps away, two strangers separated in age by 46 years lobbed a ball back and forth across roughly the same number of feet.

Chris Barber, 26, who had been prompted to attend by his mother, arrived at the park in an uncertain moment in life. He is unemployed and searching, itching to get to California to find his future. His throwing partner, David Boldrick, is 72, happy and settled, a mechanical engineer enjoying the slow sunset of his working life.

It’s not easy to imagine another setting in which these two might have met and talked, but a connection came easily here, the arc of the ball tying them together like a string.

Boldrick asked Barber about California.

“Have you got a job out there?”

“I don’t yet.”

“What kind of job do you want?”

“I have no idea.”

Pretty soon they stopped throwing. They stood and talked. Barber offered that he’d been a chemistry major.

“You can do anything you want with that,” Boldrick said.

The players threw for an hour in perfect, springlike sunshine. Finally, their arms sore and the shadows lengthening, they circled up, wrote their names in the notebook Frank had brought, and promised to meet again soon.

As they scattered, Frank said, out loud but kind of to himself, “Isn’t baseball beautiful? It’s a piece of art, really.”

It was time to go. The Millers had an appointment to get the coronavirus vaccine. Frank threw his pitching arm around Alice and they headed off, satisfied that they’d put a little Gorilla Glue on the universe.